Newsonomics: The Problem With Digital News: Older -- Not Younger -- Readers

Oh, those young people. Ask traditional media companies the problem with digital disruption, and the older people running those companies will often point to the younger generations.

“All they want to do is watch video.”

“They’ll read snippets, but not longer stories.”

“They expect the world to be free.”

“They get all their news through Facebook and don’t even know where the news is coming from!”

Fit these generalities under the category “Everything you know may be wrong.”

For instance, take a recent report, “I Saw the News on Facebook,” on how well readers identify the source of stories. The Reuters Institute asked respondents how well they recalled the source of stories read within the past two days. It’s a U.K. study, though we can assume we’d see parallel results in the U.S., given past comparative work.

How did the readers do?

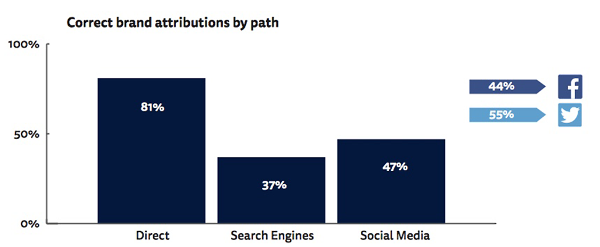

There’s good news and bad news in the results for news companies. The good news: readers identified the brands of original content producers about twice as well as when they went to those sources directly — without a Google (GOOGL) , Facebook (FB) or Twitter (TWTR) intermediary.

If they read a story on a publisher’s site, 81% could recall where it was published.

If they used a search engine or social media, the numbers, shown below, plummeted, to 37% of those who came to the story via search and 47% of those who came to the story via social.

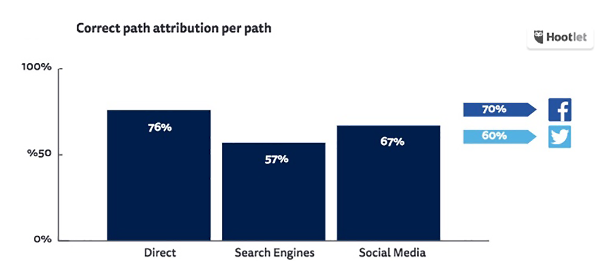

If source recognition shows itself to be far more difficult via social or search, chalk up a victory for the platforms. Respondents could better recall which platform they found the content on than the original source of it.

Sixty-seven percent could name a Facebook or other social media site as a discovery point. Fifty-seven percent could name a Google or search engine. Recognition of finding content directly on a publisher’s site still came high, at 76%. Unmistakably, though, platforms clearly gain branding value — call it mnemonic value — from the news content they distribute.

Clearly then, the study raises more questions about the value of platform distribution, even as Facebook Inc., Twitter Inc. and Microsoft Corp.’s (MSFT) LinkedIn all make further forays to become content destinations.

How much of the consumer valuing of original news is captured by the platform — and retained — and how much actually gets passed on to the publisher?

Further, the study does affirm that brand-differentiating customers — of course, at best paying, subscribing customers — offer the most value in the digital age. Those that come direct recall the brand best, and recall it more easily from social and search platforms.

The Problem With the Web: Older People

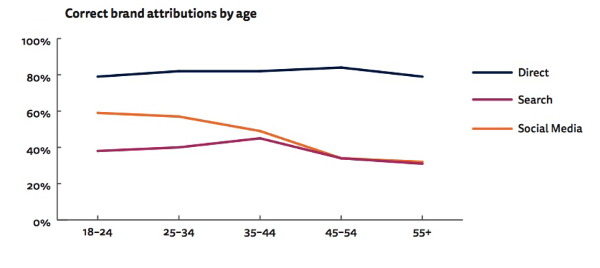

Perhaps most surprising, it’s the younger readers who are far more discerning of source than older ones. At its most extreme, younger readers — those under 44 — were doubly better to correctly recall their sources. By as much as a 40-percentage point difference, those under 44 divined the sources of their news better than those older.

Why?

“We’ve done quite a lot of work for the last couple of years. … Young people are sort of triangulating much more between social media and search and news sites,” said Nic Newman, an associate at the University of Oxford’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

“And we find that consistently. So younger people are just much more digitally literate, effectively. They are constantly triangulating everything.”

Newman, a journalist and alumnus of early BBC News innovation, said it’s a matter of picking up digital code.

“They’ve grown up with it,” he said. “They are used to using and understanding all the different signals in social media and what they mean, and the changes within social media. It’s all those kind of things I think.”

Those clues include branding, which is so unevenly and haphazardly indicated on the platforms.

It is older people — especially baby boomers — who seem most befuddled. While they clearly understand the old demarcations of brand — pages fitting within newspaper and magazine formats — they’re more flummoxed with their social and search excursions. All generations, save the oldest cohort, have jumped onto and into the internet, but for those seemingly most experienced with understanding the meaning of traditional news brands, the transition seems to be tougher than we’d thought.

(We are left to wonder how much the social/search source confusion abetted the cascade of fake news acceptance that enveloped the U.S. pre-election. It was, after all, the same older voters who disproportionately opted for Donald Trump. In Britain, older votes by large margins approved Brexit, with social media, factual and otherwise, playing a significant role.)

Who Benefits the Most From Social and Search Distribution?

In addition, the Reuters Institute research supports the notion that large, well-known, well-trusted brands do better on recall than lesser, newer ones.

In fact, they may receive some “halo” credit, as readers associate good reading with their favorite news brands even though that source didn’t really deserve the credit.

That human recall cut both ways, both overestimating known brands and underestimating less well-known ones.

“The ones that did least well were ones that had very little loyal traffic, essentially,” Newman said. “So what that says to me is that those brands that are able to have loyal relationships, and build up and invest in those over time, are the ones that are likely to do best in distributed and nondistributed” news content.

That understanding poses a big question about the value of social media for news brands.

Big brands also have lots of news cred, and it’s not clear the monetary value they can harvest from more on that on Facebook.

Then there are those news and media companies that rely on social for a disproportionate amount of traffic — having a less loyal, less direct-to-their sites customer base. Does Facebook help them as much as they think and hope that it does?

Newman said the research details that issue: “The difficulty remains, if you don’t have many loyal users, how do you bring them into your world? Just by exposing people, that’s not going to necessarily lead to a subscription or higher premiums; you’re going to need to have that relationship.

“It feels to me that the key is that publishers need to build up their loyalty with people. They need to invest in that.”

Who Is Most Likely to Pay for Digital News?

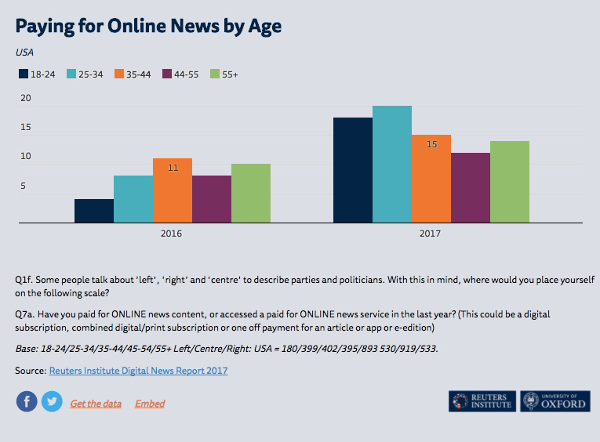

But it’s older people who are the only ones paying for digital news media products, right?

Not so, says another study from the Reuters Institute, as the chart below shows.

It is 35-to-44-year-olds who have emerged as a key buying group. Forget “the internet wants to be free.” That’s so 1999. It’s not just news of course. A higher proportion of Millennials and Gen Xers buy Netflix subscriptions than do older generations. (In fact, Netflix wants to “get older,” a key part of its strategy in just signing up David Letterman.

Further, on the video use question, it turns out younger readers may more greatly value old-fashioned words than moving pictures online.

“While 46 percent of Americans overall say they prefer to watch the news over reading it, that number is far lower for Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 — only 38 percent of that group named video as their preferred news consumption format,” a Pew Research internet report said last fall.

Put Newman, a longtime student of digital experience, as cautiously optimistic, especially about younger news consumers.

He calls younger consumers of news skeptics, that in an age where well-placed skepticism may well be valuable.

“They are more skeptical, I’d say, than the older groups in general. It’s not like they blindly trust all the brands. … That’s partly because they see things in comparing what’s going on between social media and search and other brands. They do a lot more comparing.”

“I still think the cues should be stronger within social networks,” he said. “And I know that Facebook and Google and others are trying to deal with that this year, and I think that’s an important one in terms of the trade and balance between publishers and platforms. I think it’s in the interest of social networks and Google and others for it to be clearer because I think that business will do better if it’s clearer what’s good and what isn’t good.

That lack of clarity causes anxiety in this still emerging digital age.

“Young people are also much more skeptical of traditional brands. And they are confused and stressed. You know, the whole way in which news comes to them is confusing for young and old people. And I’m not sure how healthy that is, so that’s sort of slightly less optimistic.

“[Yet] the fact that young people pay for stuff — stuff that speaks to them — is good, whether you’re talking about news or you’re talking about media generally.”