The Newsonomics of the Kochs Rising -- and Uprising

Related posts: The Tribune’s Metro Agony, The Koch Brothers and the Sale of the U.S. Top Metros, Rupert Murdoch’s Long Game

First published at Nieman Journalism Lab

It’s official. Charles and David Koch think Warren Buffett may be right.

After only sideways confirmation of their interest in buying the Tribune papers, Charles Koch on Wednesday explained the brothers’ newfound interest in newspapering to one of his favorite outlets, The Wall Street Journal.

“We wouldn’t be interested in putting huge amounts of money in it on the bet that we can have a miraculous [newspaper] turnaround,” he told the Journal. “We see it continuing to decline, the print media.” That’s an echo of what Warren Buffett recently told his annual Berkshire Hathaway meeting shareholders.

“We’re in parts of the paper industry [Koch’s Georgia-Pacific unit, acquired in 2005] that are declining,” Koch said, “and because we have a big enough competitive advantage and we’ve innovated enough, we’ve been able to continue to be commercially viable.”

Beyond the investment rationale, Koch played the editorial card: “There is a need for focus on real news, not news with an agenda or not news that is really editorializing.” It’s the editorial page that would be re-energized, said Koch, saying that those pages of papers he acquired “would be a marketplace of ideas where all sorts of approaches to public-policy issues are vetted and contrasted, and there could be ongoing debate.”

This public confirmation will only fuel the fire of anti-Koch protest. The people who funded the Tea Party (vintage pre-Veep Frank Rich on the Koch/Tea Party connection here) are seeding citizen protests of their own.

Those protests are numerous and noisy, the second indication of readers-in-the-streets outrage, which we first saw as New Orleans’ Times-Picayune cut days of print and home delivery. Mostly, they’ve been centered in L.A., though we’ve now see small crowds in a dozen cities around the country, and even a notion of a crowdsourced Tribune buyout fund. The shouts have even been taken to Tribune board chairman Bruce Karsh’s L.A. home; David Freedlander describes the nuances of applying such pressure in his Daily Beast story.

The Kochs are clearly a top potential buyer in a Tribune company sweepstakes, the likely sale of the fourth largest U.S. newspaper company (by revenue) and 11th largest in the world. We must still say likely because the Tribune Company has not yet formally committed itself to a sale, nor has it issued the “data books” that would-be buyers can comb through. Tribune has noted that 40 parties have expressed interest in its properties.

Will the company actually open up an auction? It probably couldn’t ask for better timing. The board has the possibility of competitive bidding, the ability to cite Buffettonian investment wisdom — and they know that the further crashing of print advertising in metro markets will only further decrease values if they wait too long. And as financiers, they’re short-term holders, not operators.

There’s one big complication of the moment. Two of Tribune’s three owners — Oaktree Capital Management and Angelo, Gordon & Co. — each invest lots of labor pension money; for detail, check out Matt Taibbi’s Rolling Stone piece. The burgeoning union protest, which will now grow with the Koch statements, poses conflicting pressure points, points that may lead to a non-Koch deal if the competitive offer is good enough.

The papers involved are mainly big ones (“The Newsonomics of the Tribune’s Metro Agony“). Naming some of them — the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune, the Baltimore Sun, the Hartford Courant, the South Florida Sun-Sentinel, the Orlando Sentinel — gives you an idea of why voices are rising. In America, a land of traditionally strong regional newspapers with only three national ones, such nameplates have dominated their regions for decades.

So let’s look at the newsonomics of the Kochs walking further into the public limelight — and of the uprising opposing it. Let’s doing a little sorting out of the money and the power here, and the intertwining of the two. There are some certainties involved in a would-be takeover, and then some good guesswork we can add as well.

The players

Let’s start by putting the now-public Koch interest in perspective. As the Tribune board finalizes its selling options, what are its alternatives?

Responding to the Koch protests, new Tribune CEO Peter Liguori has said that speculation on who might buy the papers is “premature.” It’s premature until data is released and orders taken, but by then, the decision could come quickly.

The new board’s mandate, of course, is to maximize its take on the sale. Tribune newspaper profits run at the roughly $200 million level, maybe a third of which comes out of L.A. So, take the market multiple of 3 or 4 times that number as a price — or $600 million-plus — for the eight papers, even though underfunded newspaper pensions put a drag on that number. Then, if the inflamed passions, stoked by the Koch bid, produce a higher selling price, so much the better.

The board clearly is aiming for a single deal. One deal reduces transaction costs and deal risk, and speeds closing. So who’s likeliest to play in a single auction for the eight Tribune papers, which also include two non-metros in Newport News, Va., and Allentown, Penn.?

The likeliest four: the Brothers Koch, Rupert Murdoch, the B group from L.A. (Eli Broad, Ron Burkle, and Austin Beutner, a well-connected trio of moneyed liberal lineage), and Aaron Kushner’s 2100 Trust.

Both the L.A. group and Murdoch are most interested in the L.A. Times, but have sent signals they might take all the papers — at least temporarily — to get the Times.

As in some sales, there’s the usual question: Is Rupert Murdoch really a serious bidder? The old press lion still can cat-and-mouse with the best of them.

Rupert, no: Explaining that his ownership of two L.A. TV stations would get in the way of an L.A. Times buy, because of FCC cross-ownership rules: “It won’t get through with the Democratic administration in place.”

Rupert, sí: Explaining the spin-off of his company’s newspaper assets, as of June 30, into a standalone News Corp.: It’s an “extraordinary opportunity that most people don’t get in their lifetime to do it all over again.” Bolstering the opportunity: the new News Corp. starts its engines with $2 billion in the bank — and no debt.

The mature business decider vs. the young “bet the company” buck.

At 82, Murdoch is unlikely to get another shot at the Times. It’s both a fitting crown and platform for the man who is becoming chairman and CEO of the other News Corp. split-off entertainment conglomerate 21st Century Fox. In Hollywood, the talk is more about the head of a major studio heading one of the top media companies covering the film and TV businesses than it is about the L.A. Times’ news credibility going forward.

Murdoch’s L.A. TV licenses come up in 2014, so the cross-ownership issue is immediate and real, and with the FCC in appointment limbo, he’ll not get the waiver relief his lobbyists had hoped to win by now. Flip a coin and I say Rupert goes with his gut and bids.

If he indeed goes for the Times (and other titles, if necessary), consider that Murdoch couldn’t ask for a better competitor than the Koch Brothers. No one’s out in the streets protesting a Murdoch takeover of the L.A. Times or Chicago Tribune. Even Koch opponents whisper that Murdoch would be better — the gray, if not white, knight, to the black hats of the Kochs. It’s a new parsing in the post-Sam Zell era: How do you judge potential ownership these days, except on a relative basis?

At least, goes this thinking, Murdoch is a newspaperman. The only other newspaperman in that group is newbie Kushner. His company bought Freedom Communications and the Orange County Register last year and has initiated the most ambitious and contrarian turnaround in the nation.

Kushner differentiates current newspaper owners from potential buyers like the Kochs. Noting that they’ve been in businesses like paper and natural gas that few people pay much attention to, he wonders whether they really want to take on the quite public glare of newspaper ownership. “There’s a big difference in writing check [for acquisition] and accepting responsibility for a community institution,” he told me this week.

Beyond L.A.

Though the Kochs’ interest seems to be for the papers as a whole, whoever wins the papers overall could then turn around and sell whatever pieces they didn’t want.

While so much attention has focused on the L.A. Times, the Chicago Tribune’s brand and pedigree would seem to be of next interest.

While the Sun-Times ownership has been named as a possible buyer, and consolidator, of the Tribune, its recent travails seem to indicate that potential is overblown. Having had some issue with paying the Tribune for its own printing, which it outsourced two years ago, and then making news last week that it laid off its entire photo staff, where would it find the money to buy the Tribune? Perhaps out of another financial pocket — but the deepening metro print ad loss has to give any financiers pause.

The Baltimore Sun — a prime rebuilding job given that it has been hollowed out by cost-cutting, would interest several local buyers — including the Abell family, one-time Sun owners and operators of the Baltimore’s leading local foundation. The Allentown and Newport News papers are properties in the sweet spot of the Warren Buffett-redefined market. Which would leave the two Florida papers — both major outlets in one of the most swingy of electoral swing states. If you’re the Kochs, or someone else with a political agenda, you might think that the ability to swing some tens of thousands of Florida voters in a presidential or Senate election could be more than worth the small price of operating a struggling newspaper or two.

We’re hearing the expected debate about what kind of investment, financial or otherwise, this would be for the Koch Brothers. That’s silly. They didn’t get to the sixth and seventh places on the Forbes 400 list by betting on business models with more seeming downside than upside. The only way to read the Kochs’ interest is “civic” from their own perspcetive or “political” from those of their opponents. Even Warren Buffett, in defending his purchase of daily newspapers at the April annual Berkshire Hathaway meeting put it bluntly: “It’s not going to move the needle at Berkshire. We wouldn’t have done it in any other businesses. There’s no doubt about that.”

For the Kochs, the purchase would be a seem to be an extension of their political wars by other means. Of course they protest that notion, and the only track record we have to go on is their profound influence on conservative activist American politics over the last several years.

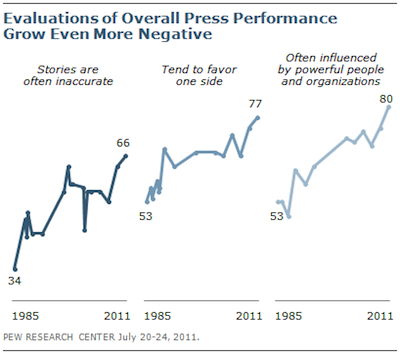

On the face of it, and a reason we’ve seen the modest uprising opposing the Koch bid, political buyers pose a larger problem for the American press. The post-World War II press has been trained and self-taught to report straightforwardly, without political intent. The press itself has always had a devil of time explaining its penchant for accuracy to the general public — witness its continuing credibility woes. It depends on such satirists and media critics as Stephen Colbert to sum it up in stunningly simple form:

On the face of it, and a reason we’ve seen the modest uprising opposing the Koch bid, political buyers pose a larger problem for the American press. The post-World War II press has been trained and self-taught to report straightforwardly, without political intent. The press itself has always had a devil of time explaining its penchant for accuracy to the general public — witness its continuing credibility woes. It depends on such satirists and media critics as Stephen Colbert to sum it up in stunningly simple form:

Truthiness is tearing apart our country, and I don’t mean the argument over who came up with the word. I don’t know whether it’s a new thing, but it’s certainly a current thing, in that it doesn’t seem to matter what facts are. It used to be, everyone was entitled to their own opinion, but not their own facts. But that’s not the case anymore. Facts matter not at all. Perception is everything.

So, in our topsy-turvy world where the jesters are the best ones able to easily spell out the truth(iness), we have this strange phenomenon of Colbertian facts — with the Koch Brothers perhaps now claiming a piece of the fact business.