Newsonomics: Fake-News Fury Forces Google and Facebook To Change Policy

Can the presidential election result be blamed on failed algorithms? Facebook had taken the brunt of that claim in the days of shock following Donald Trump’s election. Then, on Monday, Google stumbled into the fray, and by the end of the day, it’s own mini-outrage produced a significant change in how Google does business.

What’s the incident that lit the fire?

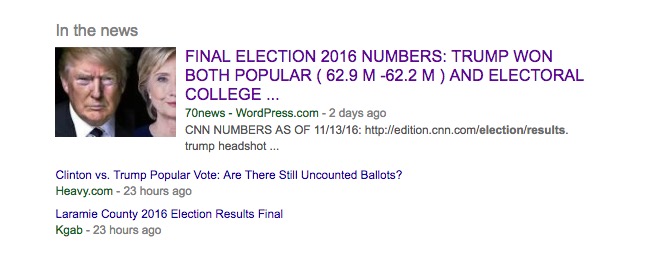

The Washington Post’s Philip Bump did a great job of tracking down a daisy chain of fictions. A site called 70News.com (“sharing news that matters to you”) had published a story claiming, falsely, that Trump had actually won the popular vote, not Hillary Clinton. Google had included the story in its news index, for some reason, and placed it prominently atop its search results for “final election results.”

That action, of course, caused the story to circulate even further and attain, what Stephen Colbert might have jokingly called, in a less tense time, “truthiness.” It was a major embarrassment, coming at a bad time; Google’s misstep, for a brief digital moment, took the spotlight off Facebook, diverting attention from its rival’s woes.

What Google had inadvertently done: taken the little lie of Donald Trump’s non-existent popular vote win and turned it into a Big Lie, through the power of its ubiquitous search engine. Then later on Monday, that Big Lie apparently forced what may be an abrupt change in Google policy. Last night, Google announced it would not allow Google-served advertising on sites that “misrepresent, misstate, or conceal information.” Nine years ago, the news industry first asked Google to clamp down on pirated news content — spam blogs — by withholding access to its ad network. Now, that same approach was being applied to the propagandists pretending to be news purveyors.

Not to outdone, Facebook then tried to move beyond its own stumbles, after well-meaning CEO Mark Zuckerberg had done poorly in explaining Facebook’s role in the Trump victory. Its solution — also announced hurriedly on Monday, after Google’s announcement — parallels Google’s: It would no longer let “misleading, illegal or deceptive site” news sites use its own Facebook Audience Network.

Together, the two announcements tell us that this bizarre election season has apparently produced a collateral benefit. In these unpredictable times, a series of fortunate events are emerging unexpectedly.

First published at Harvard’s Nieman Journalism Lab on Nov. 15

Let’s consider what led up to Monday’s moves by the two companies that now dominate much of our digital world.

As the nation woke up (and has kept waking up) to Trump’s victory, fingers started pointing understandably and immediately. Democrats ID’d the many parents of the loss: overconfidence, a poor get-out-the-vote strategy, Vladimir Putin, James Comey, and more. All are true — and so was a finger aimed in Facebook’s face.

As criticism of Facebook’s role in spreading cascading mistruths grew, Zuckerberg hit a trifecta in his handling of the criticism: clueless, defensive, and incoherent. Zuckerberg first pretended that Facebook had no impact on the election, and then starting saying things that seemed ripped from scripts for HBO’s Silicon Valley. (Though, in real life, let’s not forget, alt-right rage harasses the show’s stars.) While he called the notion of his hugely influential company influencing the election “crazy,” his own staff took exception to that characterization — and reportedly began plotting how to do better.

After that initial statement, Zuckerberg more fully defended Facebook on Facebook, and I had to laugh when I saw his use of numbers. “Of all the content on Facebook, more than 99% of what people see is authentic.” Given Facebook’s incredible volume of “content,” that 1 percent is a lot of crap. It’s also a ludicrous number for tech executive to offer up: Can you imagine if Facebook prided itself on an site performance uptime of 99 percent? (99.9% is a minimum point of acceptability, such as it is, for most news publishers.) Accuracy has often been a stepchild of runaway digital innovation, and in that 99% number, we can see how things that have real-world implications can go so badly awry. Uptime is more important than accuracy. That tells us reams about the world we’ve made, as it has emerged through the digital mixmaster.

Of course, Facebook and Google had an impact on the election, but no algo in the world can tell us how much of one. And that’s the big point here. Sure, we really want to see Donald Trump’s taxes, but even more, we want to see inside the algorithms of Facebook and Google. These two companies dominate our time (Facebook alone claim almost an hour a day of it) and have created a duopoly in digital advertising, a collateral damage of which is the destruction of print advertising, which is leading to the increasing extinction of the American (and European) journalist.

But it’s their role in fake news that has now compelled new attention — again, bringing these longstanding issues to a head — and that brings us back to that black box of algorithms. As I noted last spring when Tea Partiers attacked Facebook’s alleged bias in its Trending section, the notion of perfect, machine-like objectivity in any news presentation is a fiction. Either you have human beings, a.k.a. editors, making those decisions, or you have algorithms making those decisions. And who writes the algorithms? People. Even as we develop smart machines writing their own algos, people had to create — and program — those smart machines.

To pretend otherwise is folly, and just downright silly. Don’t let esoteric questions about human/machine interface confuse you. We’ve seen numerous Internet companies wrestle with what it means to be a “media company” or “news company” in this rise of the platforms. Twitter and Facebook, among them, have wrestled with how much to use editors and how much to use machines. The result: The top professionals in the digital industry look like amateurs, playing in a league for which they’re near-totally unprepared.

Over the years, Google has tweaked its news filters, trying to elevate real news over fake. The company has done a better job of giving priority to real news sources in its search results, with publishers I’ve talked to happily giving it credit for that work. But clearly, it needs to do a lot more, and more quickly.