Newsonomics: The Megaclustering Of The American Local Press

People in the newspaper industry increasingly joke about the triumvirate of Gatehouse Media LLC, Digital First Media Inc. and Gannett Co. (GCI) taking over the bulk of the country’s 1,350 daily newspapers as conglomerate Gannett-Gatehouse-DFMCo. Today, those three companies own a full quarter of the nation’s dailies, as family-run operations dwindle and final generations of newspaper-owning families look for the exits before the passageway becomes too narrow.

At the 25% level, we may seem like a long way away from Gannett-Gatehouse-DFMCo, but a newer phenomenon — megaclustering — moves the industry closer in that direction.

Take industries from pesticides to breweries to sporting goods, where consolidation of “maturing” industries has made some people lots of money. In centralizing and regionalizing every operation they can, consolidators manage to cut costs aggressively and make consistent profits. Bigger chains now embrace that strategy with more fervor as the pace of newspaper property sales has quickened.

First published at TheStreet on July 25, 2017

Follow Newsonomics on Twitter @kdoctor

Further with potential-to-likely changes in federal strictures on combined broadcast and print ownership and of changes in antitrust regulation itself, the phenomenon, deemed megaclustering by major newspaper business broker Dirks, Van Essen & Murray, could become even greater. That potential increased Monday, July 24, as it was reported that House Republicans had made a priority of eliminating those cross-ownership rules, as the Federal Communications Commission begins reauthorization hearings.

Megaclustering builds on “clustering.” Newspaper mogul Dean Singleton is most credited with the principle, though sharp observers believe that Thomson Newspaper CEO Stuart Garner may have been earlier responsible. (Garner, interestingly enough, made one of the great killings in newspaper sales, completing the biggest sale of its time, about $2 billion for the Thomson chain in 2000 — at the height of newspaper company value.)

Singleton built MediaNews Group Inc. on the clustering principle, and its successor company Digital First Media still operates on that principle in both the Bay Area and Los Angeles. Early on, that meant centralizing printing, personnel and back-office functions for separate — but usually contiguous — newspaper properties in the ’80s. Later, we saw editorial centralization as well.

Today, as many of those efficiencies have been absorbed, and chains look for ways to maintain profits as revenues continue to dive, megaclusters have swept the landscape. So a megacluster is what sounds like: putting an even bigger group of dailies over a wider geographic area.

It’s a logical operational step in an industry that is half-clustered.

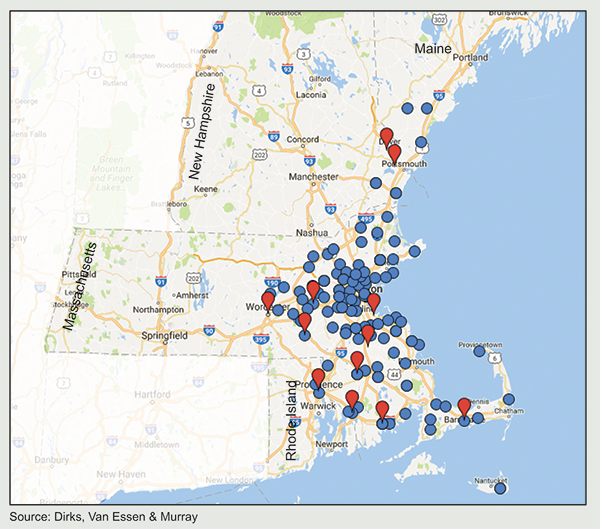

“In 1990, 15 percent of all daily newspapers were owned in such a cluster,” said Dirks, Van Essen & Murray vice president Sara April. “By 2005, 40 percent were held in a cluster. Today, nearly 50 percent are.”

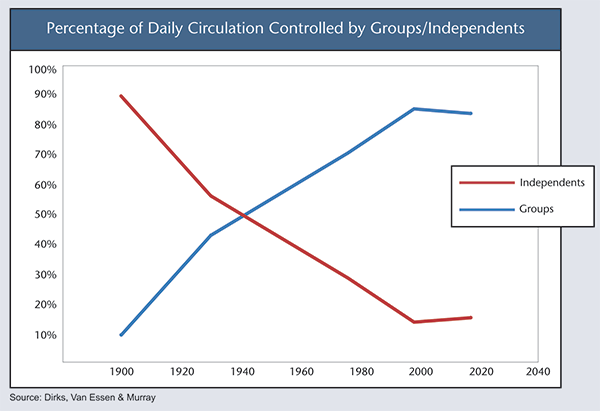

The ownership data will disabuse anyone with lingering romantic notions of family ownership of dailies. In fact, the chart below, provided by the broker, shows that chains long ago surpassed families as owners, and now control nine out of 10 dailies.

“You run out of tools,” April summed up succinctly. So if it’s harder and harder to squeeze the turnip, buy more turnips, ones snug up against the ones you already have.

This is a chain effect. First, family owners feel more pressure to sell.

“We’ve spoken to a number of families recently that own a single legacy daily,” April said. “It is tough. It is definitely tough for them. Wringing out some of the things, circulation, going through the restructuring process, you know, a lot of folks are coming to the end at what they can realize with that. Also, with the outsourcing of printing, you may be left with a building that you don’t need all of anymore. Considering what to do with that, sell it or separate it from the company. All of that. There’s a lot of companies with a lot of extra square footage.”

So the chains make the families an offer they can hardly refuse, offered a low price as they are surrounded in the marketplace. And now, the chains, feeling the same the-old-cuts-aren’t sufficient pressures, fill out their clusters with the megaclusters, and inevitably buy smaller chains.

To be sure, there’s still lots of profit in the daily newspaper business, from higher single digits to 25% or more among the chains. Properties sell consistently for 3.5 to 4.5 times companies’ Ebitda. With cost savings, new acquisitions can fuel another two to three years of relatively expectable cash flow.

April says Dirks, Van Essen & Murray’s second quarter has been among its busiest — and more business is the pipeline.

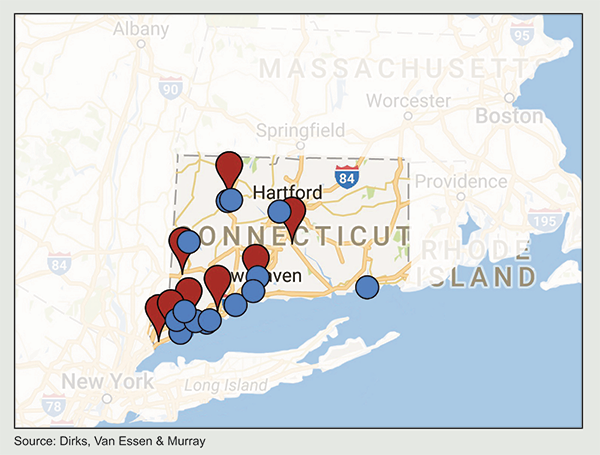

If the dots on the national map get scrutinized for clustering and megaclustering, two big political quakes could shake them much looser: A change in antitrust enforcement and a change in cross-ownership rules.

For decades, the Department of Justice’s antitrust division has enforced the rule against one company owning two dailies in the same metro area. Just recently, Tronc saw that rule stop its bid to buy the Chicago Sun-Times because it owns the Chicago Tribune; a year earlier, the DOJ stopped Tronc from buying the Orange County Register because it owns the L.A. Times.

Los Angeles and Chicago are just two of the big markets where an elimination of that antitrust rule would have a big impact. Certainly, the Bay Area — with two big companies, Hearst and Digital First Media, owning all the significant dailies in the region — and New York would see a changed landscape.

The News Media Alliance, a newspaper trade group, has made a priority of changing the antitrust rule, calling it dated in the digital age. While it is unclear how active the lobbying for a change in antitrust regulation has been, the NMA has taken the opportunity to connect that cause with its battle against the national digital advertising domination of Alphabet Inc. (GOOGL) and Facebook Inc. (FB) .

Given all the action in the marketplace and in the regulatory bureaucracy, investors may well watch the remaining public newspaper companies, with an eye toward whether they may be buyers or sellers. Those include New Media Investment Group, Gannett, Tronc Inc. (TRNC) , Lee Enterprises Inc. (LEE) and A.H. Belo Corp. (AHC) . As one example, any newfound Gannett interest in a Tronc takeover would enable a Chicago/Milwaukee megacluster. Then, there’s the question of which companies — broadcaster, newspaper or new entrants — will have the financial capital and cojones to attempt new consolidations as the marketplace further opens up.

It may be a compelling argument. Antitrust law is largely based on harm done by undue market concentration. Given that news itself has actually gotten cheaper to consumers, with the advent of the free Internet, antitrust battles could be fought over advertising pricing. There, Klingensmith’s argument has lots of support. Certainly, local advertising marketplaces have profoundly changed since the analog days of newspaper monopoly. Borrell Associates Inc., which tracks local media spending, said that “local media’s digital efforts … represent an 18% share of all locally spent digital advertising.”

That hardly seems like dominance. And yet, the question of the public interest — in the form of a lively, diverse news-producing landscape — hangs in the balance here, unaddressed by antitrust law. As Bloomberg Businessweek’s Paula Dwyer addressed recently, antitrust definition may well be an artifact of the previous century.

As the industry contests antitrust, it also advocates for change in those Federal Communications Commission cross-ownership rules that largely prevent large broadcasters from owning dominant dailies, and vice versa. We can expect the now Republican-dominant FCC to push along changes in cross-ownership — through months-long public hearings and likely lawsuits — into 2018 and likely 2019.

(Satirist John Oliver recently addressed the ascendance and politicizing market dominance of Sinclair Broadcast Group Inc. (SBGI) , one company that has already benefited from relaxed FCC TV ownership rules, in a segment that already has received more than 5 million views on YouTube alone. Expect the battles to come in media ownership rules to be long and noisy.)

Is megaclustering just a phase in the seemingly eternal downturn of daily newspapers or a point of stability? Will it be like a supernova, burning brightly for a short time — before the light goes out completely? A lot will depend on old-fashioned business execution.

Clustering, or megaclustering, requires smart management, with even attention to cost reduction and product value, though too many newspaper companies have focused disproportionately on the former and seen their customer rolls dwindle. Certainly, smarter reorganization of newsroom resources is a demand of the time.

April, though, said editorial clustering is becoming a bigger part of the sales conversation. “They’ve been thinking about it more and more on the content side, especially with digital.”

In Connecticut, for instance, Hearst Newspapers now is looking widely for a editorial leader for its big stable of dailies, interviewing some top talent in the business.

Ultimately, if megaclustering is intended to provide long-term business success, it’s editorial and digital product strength that will make or break this expanded strategy. In the meantime, expect that chain/family newspaper chart to become even more dramatically lopsided.